Reflections on moving menstruation from hygiene to health

Menstrual Hygiene Day, my bloody favourite day of the year.

I’m Jen Rubli, and I work as the Research and M&E Coordinator for Femme International, a role I’ve had since 2013. We’re a menstrual health NGO in East Africa. Our work focuses on community- and education-based strategies to expand access to menstrual resources whilst tackling gendered social norms. I could talk a lot more about our and my credentials, but that’s not what you’re here to read.

We’ve been working in the menstrual health sector almost since the beginning and have had the unique perspective of being a part of its evolution from a small, disparate number of little NGOs, one researcher (right here in Tanzania, where I’m based), and no money. Fast forward to today, where East Africa boasts numerous ground-breaking research projects, a research network, and is very much leading the way in terms of national-level policies and stakeholder groups, and regional-level coalitions, all in an effort to collaborate and coordinate. It’s dizzying, really.

The case for systems for menstruation

Systems-level thinking is so important. Especially in looking at the menstrual health sector’s roots: it was ‘young, scrappy, and hungry. And in many ways, it matured in a very ragtag way, through sheer force of will. But it also grew very much out of the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector, the first to address menstruation through supplying products (primarily disposable pads) and improving WASH facilities.

From the get-go, Femme never saw itself as WASH NGO. Instead, we started off with education and distribution of reusable products (menstrual cups and reusable pads). Our narrative followed that traditional ‘give a girl (disposable) pads and she’ll stay in school.’ PSA here: that stat about 1 in 10 girls missing school because of menstruation? Totally false.

We have learnt so much since those early days. School attendance and dropout is so much more complex than menstruation, and participation is a much better measure of programme success. Being in school or at work has nothing to do with what you actually get out of it.

Menstruation happens for 40 years, and far beyond just the school setting. It happens in workplaces and the streets and humanitarian settings. It happens to many people, not just those who identify as cis women and girls, or who do not have disabilities.

We know that products and WASH facilities, whilst vital components, are not nearly enough on their own, and a more holistic (and realistic?) approach is required. Whilst the onus is very much at the individual level, adolescent girls have no agency – giving them pads, improving access to water at school, teaching them healthy practices, these are absolutely unrelated to their ability to implement any sort of behaviour change. That comes at a community-based and systems-thinking level, and that’s where programming has to happen to see truly sustainable impact.

Those of you in humanitarian work are familiar with the cluster approach, where each expertise is siloed. But like gender, and because it is gendered, menstruation is a cross-cutting issue. It needs to be considered in WASH, in security, in lodging, in food, in healthcare. Moving beyond the humanitarian sector, it needs to be in policy, advocacy, social media, schools and workplaces, research. Like taking a gender lens to programming, menstrual considerations need to be at all levels. Which obviously isn’t to say that every menstrual health programme needs to do everything, that’s impossible. We all have our areas of expertise. This is about coordinating and collaborating to ensure we are collectively hitting all those targets.

That’s much more the approach we’re seeing today.

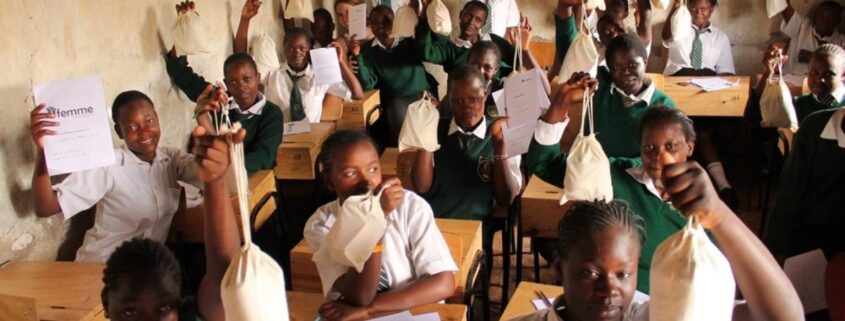

Pupils reacting to a menstrual cup.

Change is happening and more is on the horizon

Both the Integrated Model of Menstrual Experience (an evidence-based theoretical framework) and the newly-released definition of menstrual health (expanding upon the old ‘menstrual hygiene management that was completely WASH-focused), show this broader focus that takes into account the many intersecting factors that truly determine how somebody experiences and manages their period.

I’m part of two research projects in Tanzania that have done exactly this; one looking at the long-term impact on participation and health of menstrual cup users, and PASS-MHW, evaluating Femme’s school-based intervention with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit.

Our menstrual cup study, done in partnership with LUCSUS, Lunette Cup, Give a Heart to Africa, and the National Institute of Medical Research, used the framework to look at the link between menstrual cups and well-being, menstrual/reproductive health, and finances. We found that menstrual cup users suffered fewer menstrual/reproductive health symptoms and diagnoses like itching, rashes, UTIs, and bacterial vaginosis. They reported less anxiety. Why? They had increased financial security because cups result in fewer menstrual expenses. They felt safe and free during their periods, not constantly worried about leaking, smelling, or being somehow found out. They worried less about where and how they would safely change. And because anxiety and pain are part of the same feedback loop, less worry and fear meant they felt less menstrual pain. Cup users were at work more, lost less income, and had more robust social lives, missing out on fewer daily activities. Pretty powerful for a $20 piece of silicone, eh?

When you’re vacillating between cheap disposable pads that itch and burn, and cloth that leaks (so you stuff it with dried grass); when you’re choosing between a painkiller so you can be at work, or a ride to work because it hurts too much to walk; it’s easy to see the transformative power of anything that makes your period just a tiny bit easier. One less thing to worry about. So, imagine if, on top of having that menstrual cup, experiencing less pain, and being at work all day, you also didn’t feel shamed and contaminated, diminished by social norms and taboos, and restricted by sexist policies and myths.

That’s the power of using a holistic, comprehensive approach to tackling menstrual health.

If you’re interested in reading more about our menstrual cup study, follow this link: Health outcomes from using menstrual cups – A pilot study from Moshi, Tanzania

Field Stories: Social influence barriers to facilitation menstrual health workshops

Written by: Judith Atieno, Twaweza Programme Facilitator – Nairobi, Kenya

After facilitating several menstrual health workshops over the past 6 years, it is clear from our beneficiary engagements that the number one way adolescents get information is through the community. This is unsurprising and completely normal, and also backed up by data from our needs assessments. It typically involves information that has been passed down from generation to generation,

usually laden with cultural myths and taboos, and unfortunately, barely any scientific facts. This makes our job that much harder, as not only do people need more than just access to knowledge to change their behaviour, but the community and social setting need to be open and supportive to such a change.

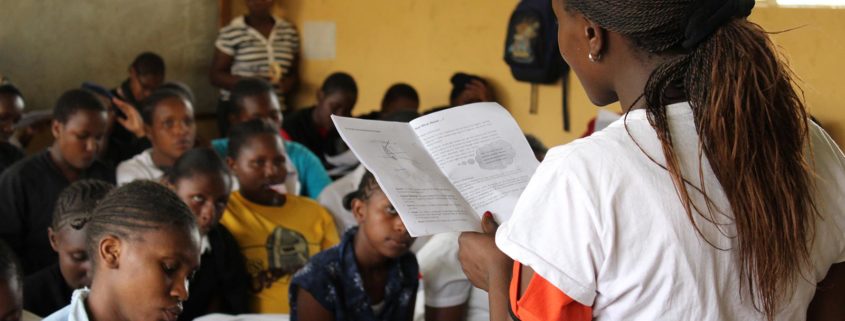

Judith engaging with students during a question and answer session of the Twaweza MHM programme, last year.

Menstruation, its experience, its perceptions and framing, and its management are drenched in socio-cultural norms and beliefs. These change from country to country, tribe to tribe, although there are some remarkable similarities. Our workshops need to be flexible enough to take these influences into account, and so we make sure to have lengthy Q&A sessions where more often than not, these social influences invariably come up.

One of the most common ways social influences come up is during the Q&A sessions, when participants ask questions about something they were told by a teacher or a guardian; they ask us to confirm if it’s true, or they try to challenge us.

Back in 2018, we ran (one of many) workshops at a school in Mathare, and distributed Femme Kits with menstrual cups (shout out to Ruby Cup!). When we return

ed for the six-week check-in a female teacher, who had also received a menstrual cup, told us she just kept her cup and would use it when she got married. The Problematic belief of aspiring merely to marriage aside, she believed that she would no longer be a virgin if she used the cup, hence the decision. This, despite the fact that she had attended the workshop just six weeks earlier, where we discussed virginity and specifically how the menstrual cup cannot, based on scientific facts, make one lose their virginity. And because of that, we made sure to stress, as always, that a cup can absolutely be used by women or girls who have not had sexual debut.

Judith teaching a Twaweza beneficiary how to wear a pad.

Teachers are both highly influential and an authority figure in an adolescent’s life, and any programming we undertake will have little effect if influencers are not also on board.

When we expect a teacher to lead by example, in some cases we end up being disappointed because they still refuse to change their attitude towards menstruation and usage of a menstrual product that needs to be inserted inside the vagina. Similarly, if a teacher is required to teach about menstruation in a class full of both boys and girls as part of the curriculum, what usually happens is that she refrains from covering the topic adequately, simply because she is influenced by her beliefs and shame because menstruation is never discussed as a topic.

Back at home, girls receive menstrual information from older women in their family, whether mother, sister, aunt, grandmother, etc., depending on both availability and tribal tradition. These older women, although they may take great pride in this responsibility, possess and pass on the same inaccurate and sometimes harmful advice, that girls then adopt, pass on, and the cycle continues.

Menstruation isn’t something shameful to be kept silent, but instead a gateway to reaching a community or group and a platform to broaden the conversation and address greater women’s rights issues.

When it also comes down to sexual reproductive health and rights education, you find in some area you are restricted from discussing the topic simply because you will be influencing bad behaviour to girls. The society does not notice the increase in teenage pregnancy every year and use of emergency contraceptives, therefore need to SRHR education in schools as low as primary schools.

Twaweza facilitators Judith(Left) and Emma pictured with Twaweza beneficiaries in Loitokitok last year.

These examples highlight the need to create menstrual programming that addresses these influences at different levels, priming the environment for behavioural change so that workshop participants are able to take the information on board and be in a supportive environment that is conducive to necessary behaviour change.

At the same time, we need to make sure that menstrual programming is accessible and relevant to all the different tribes and groups, inclusive to the countless beliefs and practices, tackling harmful myths and practices whilst being able to effectively support positive change and impact.

We, as societies, cannot succeed when half of us are being held back!

Guest post by Júlia & Antonio, Founders of Periodo Solidario

Here’s to education, and to making sure that every girl has a voice and can stand for herself.

At Periodo Solidario we are fully aware of the struggle that millions of women and girls face around the world (in our own society and also in developing countries) as a consequence of the lack of menstrual hygiene products and education.

Periodo Solidario was born under the purpose that all women and girls should have the right to a healthy and positive relationship with their bodies and direct access to menstrual hygiene products to live as healthy as possible. We are a humble small NGO that tries to do as much as possible with the limited resources we have, and we dream big.

The Periodo Solidario Faircup. Proceeds are donated to Femme International.

Taking this idea as a starting point, we created this feminist project because, from our position, it was obvious we needed to do something about it. We started doing research and concluded how overpriced the menstrual cups are in Europe. This gave us the opportunity to think about how we could create a high-quality product that was accessible to everyone and helped the NGO gather funds to make a life change to those girls that most needed it. After months of financial planning, legal struggles and a lot of designing we achieved our objective and launched FairCup.

We then did vast research on which actions could help the most, this urgent need became more visible. We also understood the incredible potential that economic resources have on these projects that work with millions of girls in an interdisciplinary way. After discussing all the possible actions, we decided we wanted to use 100% of the NGO’s profits to help create the positive impact we were looking for.

We searched for an organization that helps women, acts according to the interests of the local communities and studies its impact rigorously. That’s why we chose Femme International as the first NGO we wanted to support. Their 7-year work on more than 11.000 girls across Kenya and Tanzania and the benefits found on the Twaweza project made us realize we had met an organization that clearly is as passionate as we are about changing people’s lives.

Florence Akara, pitching the case for economic and environmental friendly menstrual products in East Africa.

We had the first conversation one year ago with Florence Akara, the managing director at Femme. Her interest in our project and her motivation in the ones she was running made clear that Femme International would be a good partner for Periodo Solidario. At the same time, we were introduced to Rachael Ouko, the Nairobi office manager, who explained her experience at Femme and shared her will to break down the stigma and normalize the natural process that is the menstrual cycle.

We have since then been collaborating with Femme International while working to sell more menstrual cups, gather resources and make a real change. We also believe that sending our profits to Femme is the best idea to support the local communities. Given we advocate for sustainable menstruation products and we aim to reduce as much as possible our CO2 emissions (due to the means of transportation), we decided to transfer our donations instead of physically sending our product to Africa.

Femme beneficiaries with their workbook and Femme Kit complete with a menstrual product of their choice.

Moreover, by giving more Femme Kits, we are encouraging women to be able to share different knowledge by providing an open and secure space to engage in discussions about menstrual health and hygiene and other topics that tend to be socially controversial in most societies. At the same time, we have reached out to a lot of girls by developing an active webpage and Instagram account where we publish educational information, tips on how to use the cup, news, and suggestions on how to deconstruct social prejudices and stigmas surrounding women’s body.”

We are very grateful to be a part of this amazing association. Our most deep respect for the amazing people that work to ensure every girl can meet her rights and access to the same opportunities as men do.

We cannot wait to share this journey with Femme and keep working together to end #periodpoverty!

The “othering” of homeless women and girls is usually naturalized, perpetuating their marginalisation.

Guest post by inspiring superwoman, Elizabeth K. Gimba from “Go with the Flow, Period!”

I am Elizabeth K Gimba from Kenya/South Sudan and currently reside in New York, USA where I am pursuing a major in Neuroscience and minors in French and German. There is an impressive latitude of things I am passionate about; menstrual poverty and its alleviation is one of them.

Last year, I was privileged to be a grant recipient while studying in Freiburg, Germany through one of my projects “Go with the Flow, Period!” on sustainable menstrual cups for homeless women and girls in Nairobi, Kenya. I partnered with Femme International, an organisation that persistently champions for menstrual rights in different regions around Eastern Africa. The project’s aim was to facilitate menstrual education and distribution of sustainable menstrual cups to homeless women and girls in the streets of Nairobi, Kenya and that is exactly what Femme International, and I spent the June of 2019 doing.

We used Twaweza Program workbooks courtesy of Femme International in both English and Swahili to ensure an optimum comprehension of what we would be training the women and girls. The workbooks covered vital topics on the female reproductive system, puberty, personal hygiene, menstruation and the menstrual cycle, managing and tracking periods, Pre-Menstrual Syndrome (PMS) and how to manage it, problems associated with menstruation, Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs), Reproductive Tract Infections (RTIs), reusable pads, menstrual cups and more.

Beneficiaries of the project funded by Elizabeth Gimba at a shelter in Mlango Kubwa,Nairobi, where an NGO called Joy Divine is helping to house and feed street youth.

I was inspired to carry out the project in the streets because the “othering” of homeless women and girls is usually naturalized thus further perpetuating their marginalisation. This meant that my aim was not only to confront the daily silent necessities of period poverty but to also restore the dignity that all women and girls on the streets rightfully deserved.

Moreover, the project enables us to learn more about the life of menstruating, homeless women and girls through emic perspectives and experiences. Distributing menstrual cups which could last the women a period of up to ten years was one of their inflection points. For most women and girls, it was their first time learning about menstrual cups and this made both our experience and theirs more meaningful. Additionally, as the menstrual cups came in Femme kits we provided the women and girls with bars of soap and at least a pair of underwear each to allow for proper sanitation during their periods.

In essence, the immediate community was very open to supporting our movement and mission and at some point also encouraged their younger daughters to join in the training we gave in order to learn more about menstrual education. This shaped to some extent their perception of menstruation in general and certainly clarified that menstruation is not a shameful phenomenon but rather something natural that they should all embrace and be proud of.

Elizabeth Gimba is the founder of “Go with the flow, Period!” and a young educationist currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in Neuroscience with French and German minors.

International Women’s Day: #balanceforbetter

Addressing menstruation is a key component to achieving that gender balance, equality, and equity at every level of society. Why? Because menstruation is too often a barrier. It casts people as dirty or contaminated and places restrictions upon them which excludes them from fully participating in their daily lives. It is an extra financial burden (think: Tampon Tax) over something that cannot be controlled.

Femme’s Judith and Emma with students at Enkijape Primary School.

Pain is the number one reason globally that women and girls stay home during menstruation. First off, they’re missing school or work. Secondly, there is a worrying lack of research into what causes period pain, and how to treat it effectively. If more menstruators were making funding decisions or sitting on research ethics committees, there would probably be more money and more incentive to research this, as opposed to turning up at a clinic and being told to ‘deal with it’.

Ever heard of the tampon tax? Or on a broader level, the pink tax? Despite a growing movement in many countries, menstrual products are often still taxed as ‘luxury’ items, while things like wedding cakes, Viagra, or maraschino cherries are not taxed. I think most menstruators would agree that purchasing menstrual products is not a choice, it’s a necessity.

The gender pay gap is already well documented, where women make less than men for equal work. And then they have to pay more for their bodies – menstrual supplies each month, or are paying up to hundreds of dollars for some type of hormonal contraception. In family settings, it is also usually women who help to pay for other women’s menstrual costs. Bottom line: women earn less but pay more.

Hiding menstrual status is key. Women slip products up sleeves, into pockets, and once in the bathroom, wait for everyone else to leave so no one will hear the package crinkling. Product manufacturers boast smaller, more discreet, quieter packaging. In many countries, it’s even taboo to reveal menstrual status to men and boys. Women and girls fear the teasing or sexual abuse they will face if this is known. The non-menstruating body is what is considered status quo, and to deviate from that is an aberration that needs to be concealed and solved. In one study, a woman dropped either a tampon or a hair clip. Afterwards, participants rated women who had dropped a tampon as less competent and less likeable than those who had dropped a hair clip. Participants also tended to sit further away from tampon-droppers. All because it was a visible reminder of her menstrual status. Now extrapolate this scenario to every day in public, where a female applicant suddenly becomes less desirable for no reason other than she happens to reveal her menstrual status.

Women are judged much more harshly than men, and by different criteria. This is compounded when menstruation is added to the mix. A study on female entrepreneurs in Sweden, one of the most gender-equal countries globally, found that female entrepreneurs are, unsurprisingly, judged on very different criteria than their male counterparts. Women who pitched were more likely to be judged on their appearance, were often referred to as needing support (or somehow lacking it), were portrayed as anxious and worried about their success, and had their competency questioned. Male pitches were much less likely to be referred to negatively. Additionally, only the men were referred to as entrepreneurs. At the end of the day, men received 52% of the venture capital they’d requested; women received 26%.

This year’s theme for International Women’s Day (IWD) is #balanceforbetter. What does that mean? It is referencing the facts and statistics that demonstrate gender equality benefits everyone – it is not just about women.

“All of these inequalities add up – women are paid less, taken less seriously, judged based on their appearance as opposed to their ability, and generally considered a less capable aberration of the default male (non-menstruating) status quo. We live in a world designed by men, for men, and it takes its toll.”

Ironically, female is actually the biological default. Male feotal development requires that specific signals be sent and received in order to develop male internal and external reproductive organs, and gender identity. When those signals are not sent or received, the default female will develop. Furthermore, XX (female chromosomes) is viable, whilst YY is not. Males are XY chromosomes.

Addressing menstruation removes one of the barriers that women and girls face. Armed with accurate and practical information, an understanding of their bodies and how it works, and the tools they need, women and girls are better able to stand their ground. When they are not suffering from shame and anxiety of leaking, they can concentrate at school and work, and be present for key moments. Energy is instead directed to excelling professionally. Women and girls are empowered every day of the month.

Period.

Welcoming our new Regional Director!

Florence Akara

Last month, we welcomed Florence Akara to Femme International’s team as our new Regional Director for East Africa! We are so excited to have her leading the organization to new levels of growth and success in Kenya, Tanzania and beyond.

Flo brings to the team a fresh perspective, experience and a deep commitment to empowering girls through health education.

Why are you passionate about girl’s empowerment?

I have personally experienced what it means to grow up as a girl in a society which, albeit giving access to education and opportunities, still boxes the expectations of what it means to be a woman. I am fortunate to have a family that has learned to accept me the way I am, which can be difficult – my concern is for the girls out there that don’t have the same support systems that I have been fortunate to have. Women have so much to offer, but, we are caged in patrilineal societies that force us to step back and evaluate how we act, behave, or speak in order to be deemed acceptable or a “good woman”. We do not unleash our full potential as a consequence. I would like to create a world where girls and women are liberated from that mindset. Where they strive to be the best they can be without any limitations.

What has been the career path that led you to take on this role?

I spent 5 years as a corporate lawyer but never felt any passion for my job. I switched countries and jobs in the hope that I would land that job/role that will lead me to that “passion”. In August 2017, I had enough of waiting for the passion to find me; I resigned from my job and sought to go find this passion. Fortunately, I found an opportunity with a civil society organisation called Chapter One Kenya. Civic activism immediately became a passion I could resonate with. After three months at Chapter One, I knew one thing – I wanted to lead movements that will create platforms through which girls and women will be involved in public policies and decisions affecting them. I did not, however, know how or where I would do this. In January 2018, I moved to Moshi, Tanzania where I lived as a volunteer for three months and thereafter visited various organisations to learn about their work. I met with the Femme International team during my stay in Moshi and immediately knew this was the kind of organisation I want to work with. There is a dire need for our societies and governments to improve policies for access to menstrual health kits and facilities as well as education. What Femme is achieving in East Africa, it’s current region of operation, is nothing short of remarkable and I am grateful for this opportunity to help Femme grow and reach more beneficiaries.

What are you the most excited about with Femme?

I am most excited about Femme’s ability to achieve up to 6 sustainable development goals by just tackling menstrual health issues in East Africa. The reusable pads and menstrual cups coupled with the curriculum training that Femme offers women and girls help tackle sustainability goals for education, health, gender equality, WASH, economic empowerment, responsible consumption and production. This is especially exciting because, through Femme, I will achieve my personal goals of becoming a sustainable development champion by 2030.

Why do you think that #MenstruationMatters?

In my senior high school, we wore yellow tunics and skirts. This was a nightmare during my cycle. My confidence levels were low and I passed any opportunities to stand before the class or explain concepts (which required standing up) because I feared I would be a laughing stock if I had stained myself. Such fears are not without merit; I have witnessed girls shredded to tears when a classful of people point and roll on the floor laughing at her – particularly boys. It is inconceivable how many women pass up opportunities because their self-esteem and confidence are overwhelmed by a fear of something that is so natural. When girls and women learn to own menstruation with confidence, talk about it openly with the support of other women, men, their families, communities and government. They will be more active participants in their societies and not let menstruation inhibit them from any opportunity.

Fast forward five years, where do you see Femme?

I see Femme International having access to girls all over the world. Leading the pack when it comes to discussing women’s matters and teaching girls how to be comfortable in their own bodies so that they can focus their energies on becoming people of substance. In addition, Femme will lead women and girls everywhere to actively participate in sustainability as they take it upon themselves to protect their environment by being mindful of the products they use and put out because they’ve been taught better.

Master thesis research with Femme International

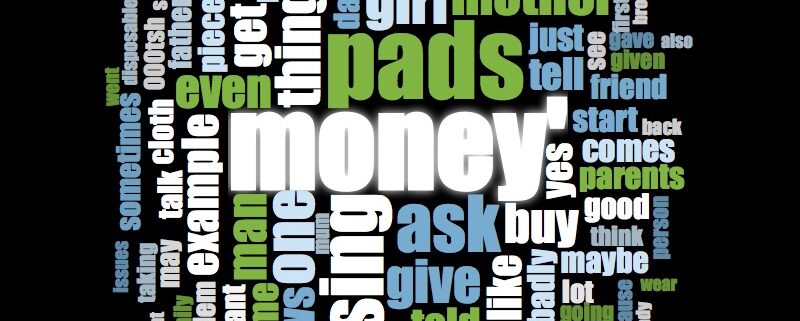

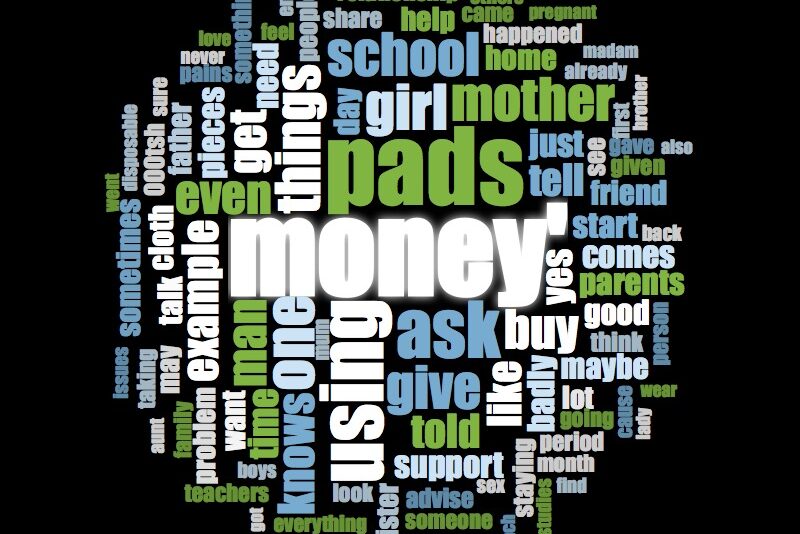

Between September and December 2017, I have conducted research alongside Femme International to collect qualitative data for my M.Sc. thesis in Human Security at Aarhus University in Denmark. In June 2018, I have finally handed it in and gave it the title “The monthly costs of bleeding – An exploratory study on the connection of menstrual health management, taboos and financial practices amongst schoolgirls in the Kilimanjaro region in Northern Tanzania”.

My interest in this field originated in the desire to understand the practice commonly described as “sex for pads” that I came across when I started to explore the connection between menstrual health and human security. Since I initially assumed this practice was a consequence of financial struggles, I started my research with a focus on the connection between MHM and financial insecurity. During my three months with Femmein Moshi, however, I realised that engaging in transactional sex or relationships is not exclusively a result of financial needs, but also connected to cultural practices, power and social structures within the respective societies. Just like most (reproductive) health behaviours, MHM is embedded in larger structures.

To understand the girls’ experiences, their voices and perspectives are central. I have gathered qualitative data to analyse various strategies that schoolgirls use to obtain MHM products or money to buy products. The main strategies I have encountered are support from family, teachers or school staff, friends and community members, work and engaging in transactional sexual relationships. Whilst these strategies all show a degree of agency, I am exploring the inhibitions through social structures and show the damaging consequences some of the girls’ methods can have. Additionally, their decision-making power is impacted by their identity, position in society and education system, other people’s expectations, and a variety of menstrual taboos.

The goal of my thesis is to illustrate the complexity and interconnectedness between MHM, reproductive and sexual health, financial insecurity, and underlying societal structures and cultural perceptions and practices. I am showing that attempts to improve MHM practices exclusively in relation to financial struggles or inaccessibility of menstrual products will fall short when underlying structures are ignored. Further, I argue that the pervasiveness of patriarchal structures entangled in Tanzanian society, the financial and economic disadvantages and the taboo of menstruation are forms of structural violence against women. They result in MHM practices that put women and girls at higher risk in terms of assault, direct violence and health problems.

For anyone interested in reading more, you can read and download the whole thesis here.

Katja Brama

Fieldwork Experiences: Menstruation, Human Security & Privilege

From experience, I have learned to give a brief definition of my field before elaborating why it is relevant in any context. The general ideas of Human Security have been around for a while but as a concept, it was made popular by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 1994. Its two main aspects are ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’ and the UNDP defines its purpose as ensuring that ‘people can exercise choices safely and freely – and that they can be relatively confident that the opportunities they have today are not totally lost tomorrow.’ It is an approach that focused on the individual rather than the nation state and consists of seven security dimensions that are all interconnected: Economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security. In an ideal – and unfortunately rather utopian – world, a balance of these dimensions would lead to a peaceful, stable and safe existence of all people and societies.

From experience, I have learned to give a brief definition of my field before elaborating why it is relevant in any context. The general ideas of Human Security have been around for a while but as a concept, it was made popular by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 1994. Its two main aspects are ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’ and the UNDP defines its purpose as ensuring that ‘people can exercise choices safely and freely – and that they can be relatively confident that the opportunities they have today are not totally lost tomorrow.’ It is an approach that focused on the individual rather than the nation state and consists of seven security dimensions that are all interconnected: Economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security. In an ideal – and unfortunately rather utopian – world, a balance of these dimensions would lead to a peaceful, stable and safe existence of all people and societies.

Although my research focus is the connection between financial (in-)security and MHM practices, my time here has taught me that connections between menstruation and all seven dimensions exist and that the surrounding cultural context is key to understanding the challenges that are a daily reality for many.

For some Human Security dimensions like environmental security, the connection to MHM is easily made: In Tanzania, trash is often disposed by burning it on the side of a road and adequate incinerators to dispose of menstrual health products correctly, do not exist.

Health security is another dimension that shows an obvious connection to MHM issues. Many WASH facilities are neither safe nor clean and the lack of access to safe MHM products leads to girls using pieces of cloth, toilet paper, gaze or extremely unsafe options like cow-dung to manage their periods. Whilst MHM products are in direct competition with other household goods, the use of those products is not only due to financial insecurities, but also connected to a variety of myths and a deep suspicion towards ‘Western’ products like disposable pads or tampons.

Katja with students at Ghona Secondary School in Tanzania

Many of the myths surrounding menstruation here are connected to personal security and community security and lead to exclusion of women and girls in a variety of ways. The most extreme example is the fear that contact with, or the sight of menstrual-blood could accidentally give people cancer, incapacitate them, curse them, make them infertile or kill them. Other myths are less dramatic but can have an equally excluding impact on the lives of people who menstruate. They are expected to not touch vegetables, fruit or water, not allowed to add salt to the meal they cook, they are refused the entrance to religious spaces, expected to not wash their hair whilst they bleed or follow extreme hygiene rituals – the list is long. One of the most damaging misconceptions in my opinion, is the assumed connection between the onset of menstruation and sexual maturity. Instead of explaining what is happening to their bodies, girls are merely taught to be ‘careful’, in other word, not to get pregnant. The attempt of managing their periods in a dignified way, for example by counting the days of their cycle, often leads their parents to the suspicion that they want to find their ‘safe days’ and have started engaging in sexual activities.

During my time with Femme, I have realized how little my own menstrual cycle impacts my life and my choices in comparison to many menstruating people living in countries of the Global South. In the words of one of my newly found friends in the Kili Hub: ‘I am in a privileged position as a menstruator’ – especially here. Nevertheless, we should not overlook that the stigma and problems surrounding menstruation are global and only enhanced in certain contexts.

Katja Brama

Introducing our YouTube channel!

Welcome to 2017!

Have you made any resolutions for yourself this year? Our team has set several goals for ourselves, as a way of keeping us motivated. This year, we want to reach 12,000 women and girls with the Feminine Health Empowerment Program across East Africa, and conduct important research about menstrual health and hygiene. One of our main goals is to find new and innovative ways of delivering menstrual health education across East Africa. This includes busting myths, breaking taboos and starting an important conversation about women’s health.

Another goal of ours is the launch of our brand new YouTube channel! We will be sharing videos from the field to show you our work and impact in East Africa, as well as short videos to introduce our team to you.

As part of our New Years resolution to deliver menstrual health education, our Tanzanian team will be sharing what they knew about menstruation before they started working for Femme. This is the first video in a series of Q&A videos with our team based in Moshi.

What did you know about menstruation before your first period?