Reflections on moving menstruation from hygiene to health

Menstrual Hygiene Day, my bloody favourite day of the year.

I’m Jen Rubli, and I work as the Research and M&E Coordinator for Femme International, a role I’ve had since 2013. We’re a menstrual health NGO in East Africa. Our work focuses on community- and education-based strategies to expand access to menstrual resources whilst tackling gendered social norms. I could talk a lot more about our and my credentials, but that’s not what you’re here to read.

We’ve been working in the menstrual health sector almost since the beginning and have had the unique perspective of being a part of its evolution from a small, disparate number of little NGOs, one researcher (right here in Tanzania, where I’m based), and no money. Fast forward to today, where East Africa boasts numerous ground-breaking research projects, a research network, and is very much leading the way in terms of national-level policies and stakeholder groups, and regional-level coalitions, all in an effort to collaborate and coordinate. It’s dizzying, really.

The case for systems for menstruation

Systems-level thinking is so important. Especially in looking at the menstrual health sector’s roots: it was ‘young, scrappy, and hungry. And in many ways, it matured in a very ragtag way, through sheer force of will. But it also grew very much out of the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector, the first to address menstruation through supplying products (primarily disposable pads) and improving WASH facilities.

From the get-go, Femme never saw itself as WASH NGO. Instead, we started off with education and distribution of reusable products (menstrual cups and reusable pads). Our narrative followed that traditional ‘give a girl (disposable) pads and she’ll stay in school.’ PSA here: that stat about 1 in 10 girls missing school because of menstruation? Totally false.

We have learnt so much since those early days. School attendance and dropout is so much more complex than menstruation, and participation is a much better measure of programme success. Being in school or at work has nothing to do with what you actually get out of it.

Menstruation happens for 40 years, and far beyond just the school setting. It happens in workplaces and the streets and humanitarian settings. It happens to many people, not just those who identify as cis women and girls, or who do not have disabilities.

We know that products and WASH facilities, whilst vital components, are not nearly enough on their own, and a more holistic (and realistic?) approach is required. Whilst the onus is very much at the individual level, adolescent girls have no agency – giving them pads, improving access to water at school, teaching them healthy practices, these are absolutely unrelated to their ability to implement any sort of behaviour change. That comes at a community-based and systems-thinking level, and that’s where programming has to happen to see truly sustainable impact.

Those of you in humanitarian work are familiar with the cluster approach, where each expertise is siloed. But like gender, and because it is gendered, menstruation is a cross-cutting issue. It needs to be considered in WASH, in security, in lodging, in food, in healthcare. Moving beyond the humanitarian sector, it needs to be in policy, advocacy, social media, schools and workplaces, research. Like taking a gender lens to programming, menstrual considerations need to be at all levels. Which obviously isn’t to say that every menstrual health programme needs to do everything, that’s impossible. We all have our areas of expertise. This is about coordinating and collaborating to ensure we are collectively hitting all those targets.

That’s much more the approach we’re seeing today.

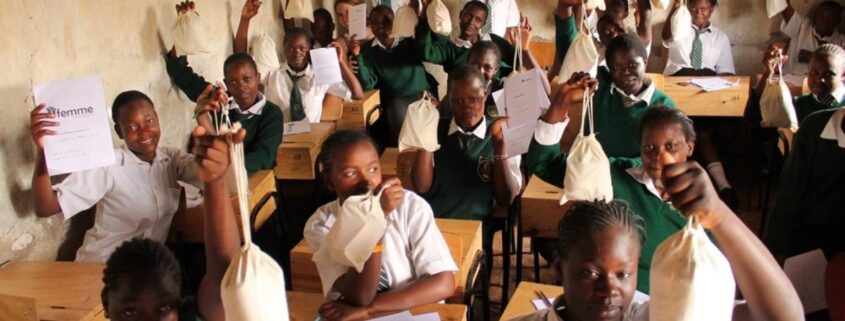

Pupils reacting to a menstrual cup.

Change is happening and more is on the horizon

Both the Integrated Model of Menstrual Experience (an evidence-based theoretical framework) and the newly-released definition of menstrual health (expanding upon the old ‘menstrual hygiene management that was completely WASH-focused), show this broader focus that takes into account the many intersecting factors that truly determine how somebody experiences and manages their period.

I’m part of two research projects in Tanzania that have done exactly this; one looking at the long-term impact on participation and health of menstrual cup users, and PASS-MHW, evaluating Femme’s school-based intervention with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit.

Our menstrual cup study, done in partnership with LUCSUS, Lunette Cup, Give a Heart to Africa, and the National Institute of Medical Research, used the framework to look at the link between menstrual cups and well-being, menstrual/reproductive health, and finances. We found that menstrual cup users suffered fewer menstrual/reproductive health symptoms and diagnoses like itching, rashes, UTIs, and bacterial vaginosis. They reported less anxiety. Why? They had increased financial security because cups result in fewer menstrual expenses. They felt safe and free during their periods, not constantly worried about leaking, smelling, or being somehow found out. They worried less about where and how they would safely change. And because anxiety and pain are part of the same feedback loop, less worry and fear meant they felt less menstrual pain. Cup users were at work more, lost less income, and had more robust social lives, missing out on fewer daily activities. Pretty powerful for a $20 piece of silicone, eh?

When you’re vacillating between cheap disposable pads that itch and burn, and cloth that leaks (so you stuff it with dried grass); when you’re choosing between a painkiller so you can be at work, or a ride to work because it hurts too much to walk; it’s easy to see the transformative power of anything that makes your period just a tiny bit easier. One less thing to worry about. So, imagine if, on top of having that menstrual cup, experiencing less pain, and being at work all day, you also didn’t feel shamed and contaminated, diminished by social norms and taboos, and restricted by sexist policies and myths.

That’s the power of using a holistic, comprehensive approach to tackling menstrual health.

If you’re interested in reading more about our menstrual cup study, follow this link: Health outcomes from using menstrual cups – A pilot study from Moshi, Tanzania